Marfan syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

[[Category:Misc/General]] | [[Category:Misc/General]] | ||

===Disposition=== | ===Disposition=== | ||

Revision as of 16:11, 27 August 2025

BACKGROUND [1]

- Marfan syndrome (MFS) is a heritable connective tissue disorder with multi-system involvement

- First characterized as a syndrome by French pediatrician Antoine Marfan in 1896

- Clinical features vary along a spectrum typical of autosomal-dominant disorders

- Autosomal-dominant mutation in FBN1 gene (encodes collagen matrix protein fibrillin-1) on chromosome 15

- This results in cystic medial degeneration of the aortic tunica media (leading to increased risk of aortic aneurysm / dissection)

- This also interferes with elastin deposition during extracellular matrix formation implicates in the elasticity of multiple tissue types

- Majority of cases (75%) are familial / inherited vs. minority (25%) are de novo mutations

- Estimated prevalence of 1/5000 individuals worldwide (equal between men and women)

- Life expectancy for those diagnosed and treated is now close to that of non-MFS population (previously expected increase in patient mortality by third and fourth decades of life)

CLINICAL FEATURES & DIAGNOSIC CRITERIA [2]

Revised Ghent Nosology (2010)

In the absence of family history:

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 and Ectopia Lentis

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 and FBN1 Mutation

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 and Systemic Score > 7 points

- Ectopia Lentis and FBN1 Mutation (associated with aortic root dilatation)

In the presence of family history:

- Ectopia Lentis and Family History of Marfan Syndrome (MFS)

- Systemic Score > 7 points and Family History of MFS

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 (above 20 years old), > 3 (below 20 years old) and Family History of MFS

Clinical Features (not all may be present) (Figure 1)

- Tall stature, long extremities

- Reduce upper-to-lower segment ratio, increased arm span-to-height ratio

- Arachnodactyly (“wrist sign, thumb sign), reduced elbow extension

- Scoliosis or thoracolumbar kyphosis

- Pectus excavatum or carinatum

- Ligamentous laxity, hyperextensibility

- Protrusio acetabuli

- Hindfoot deformity, plain flat foot

- Ectopia lentis

- Myopia (often severe); retinal detachment

- Lumbrosacral dural ectasia

- Dolichocephaly, downward slanting palpebral fissures, enophthalmos, retrognathia, malar hypoplasia, high arched palate

- Skin striae

Increased Risk of the Following [3]

- Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS)

- Thoracic aortic aneurysm

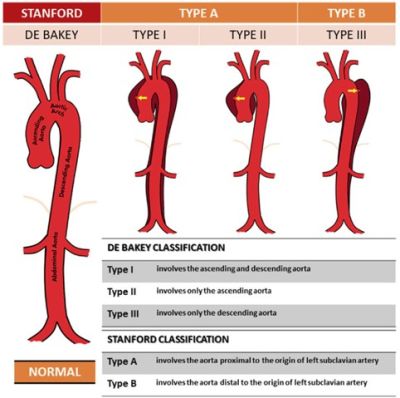

- Stanford Types A and B Aortic Dissection

- Intramural Hemotoma (IMH)

- Mitral valve prolapse (present in up to 60%) and mitral regurgitation

- Spontaneous pneumothorax (associated with bullae, 4-11%)

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)[4]

- Controversial link between Marfan Syndrome and intracranial aneurysms (more clearly associated with vEDS and LDS)

- Ocular Lens dislocation, retinal detachment

- Spinal conditions (scoliosis; lumbosacral disease; dural ectasia)

- Musculoskeletal injuries due to joint laxity (laxity in 85% of children, 56% of adults)

- Complications during pregnancy (risk of aortic dissection)

- Type A dissection risk increases with aortic dilation; Type B risk poorly understood. (aortic dissection in up to 4.5%, primarily peripartum)

Figure 2. Classification of Aortic Dissection using Stanford and DeBakey systems. Source: ResearchGate

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS[2]

- Classic vs. Kyphoscoliotic vs. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (vEDS)

- Loeys-Dietz Syndrome (LDS)

- Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection (FTAAD)

- Familial Ectopia Lentis Syndrome

- MASS Phenotype (Myopia, Mitral Valve Prolapse, Aortic Root Dilatation, Aortic Aneurysm Syndrome, Striae, Skeletal Findings)

- Shprintzen-Goldberg Syndrome

- Beals Syndrome

- Stickler Syndrome

- Non-Specific Connective Tissue Disorder

MANAGEMENT

Medications

- Beta-Blocker (BB) and/or Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Blocker (ARB) Therapy

- Beta-blockade lowers blood pressure / heart rate and reduces aortic wall shearing forces to reduce the rate of aortic aneurysm growth and risk of dissection

- Inhibition of ATII Type 1 Receptor-mediated TGF-beta signaling may reduce elastic tissue degeneration based upon mouse models.[4]

- Other Pharmacologic Considerations

- Avoidance of fluoroquinolones (FQs) due to matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation and increased risk of aortic aneurysm/dissection

- Chen S-W et al. (2023) did not show a significant increase in aortic aneurysm/dissection (OR 1.000) in MFS and other high-risk patients after FQ administration[5]

- Gopalakrishnan et al. (2020) showed a significant increase in aortic aneurysm/dissection in patients receiving FQs for pneumonia (HR 2.57, p<0.01%), but not UTIs (HR 0.99, p<0.01%). This suggests intrathoracic inflammation from the primary disease pathology, not FQs themselves, increase the risk of aneurysm or dissection[6]

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer recommended for MFS patients before dental procedures, except in those with artificial heart valves

- Avoidance of fluoroquinolones (FQs) due to matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation and increased risk of aortic aneurysm/dissection

Lifestyle Modifications[7]

- Regular blood pressure measurement, lifestyle modification, and titration of antihypertensive therapies with goal BP < 120/80 mmHg

- Avoidance of high-intensity, high-impact sports and intensive isometric activities / weightlifting

- Low- to moderate-intensity aerobic activities are encouraged after discussion with a cardiologist or specialist

- Avoidance of Valsalva and other maneuvers that increase intrathoracic or abdominal pressure (risk of acute dissection)

- Avoidance/cessation of tobacco, smoking, vaping, or stimulant abuse (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamines)

- Psychiatric evaluation, resources, and support groups (e.g., Marfan Foundation, GenTAC) as appropriate to help address psychosocial sequelae (e.g., body dysmorphia, anxiety, depression, PTSD, suicidal ideation)

Emergency Management[8][9]

- Evidence-based management of acute aortic dissection:

- IV medications to reduce blood pressure (< 100–120 mmHg) and heart rate (< 60 bpm) (e.g., esmolol, labetalol, nitroprusside)

- Emergent vascular, cardiothoracic, or other surgical consultations

- Definitive management per current guidelines based on Stanford Type A vs. B dissection, location, extent, and branch involvement

- Standard-of-care treatment for other associated pathologies

Disposition

- Disposition depends entirely upon the chief complaint, clinical gestalt, and objective findings from physical exam and workup.

See Also

External Links

- Marfan Foundation

- Marfan Foundation (Resources for Physicians)

- GenTAC Alliance

- International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD)

References

- ↑ Milewicz DM, Braverman AC, De Backer J, et al. Marfan syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):64. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00298-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The Marfan Foundation. (2025, May 21). The Marfan Foundation | Know the Signs | Fight for Victory. Marfan Foundation. https://marfan.org/

- ↑ Dean, J. Marfan syndrome: clinical diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:724-733. doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201851

- ↑ Reference 7

- ↑ Reference 8

- ↑ Reference 9

- ↑ Reference 10

- ↑ Reference 11

- ↑ Reference 12

References

- Kim JH, Woo Kim J, Song S-W, et al. Intracranial aneurysms are associated with Marfan Syndrome: Single cohort retrospective study in 118 patients using brain imaging. Stroke. 2020;52(1):331-334. doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032107